- Chang’e: The Moon Goddess in Chinese Mythology

- Myth and Legend of the Moon Goddess

- The Mid-Autumn Day and Chang’e

- Chinese Moon Myth: The Jade Rabbit in the Moon

- Guanghan Palace

- The Real Chang’e in Historical Records

- Chinese Poems about Chang’e

- Chang‘e in ‘Journey to the West’

- FAQs about Chang’e and the Jade Rabbit

- Reference

Chang’e: The Moon Goddess in Chinese Mythology

- Name: Chang’e

- Title: Spirit of the Moon, Moon Goddess

- Background:

Chang’e is one of the most renowned goddesses in Chinese mythology, embodying the spirit of the moon. Originally known as Heng’e, her name was later changed to Chang’e due to imperial naming taboos associated with an emperor’s name. She is famously known for stealing the elixir of immortality from her husband, the great hero Hou Yi, and ascending to the moon.

- Mythological Origins of the Moon Goddess:

The Chang’e myth dates back to the Warring States era (fifth century BC) with early traces found in divination texts. The story has evolved over time, gaining more complexity and rationalization. In some versions, Chang’e is said to transform into an ugly toad as punishment for stealing the elixir. In others, a rabbit, often referred to as the “Jade Rabbit,” pounds the elixir on the moon. Chang’e shares the moon with Wu Gang, who faces perpetual punishment for his wrongdoing.

- Symbolism of the Moon in China:

Chang’e symbolically represents women’s beauty, gentleness, elegance, and quietness. In modern times, she is commonly depicted as a charming and graceful figure in various forms of art and literature. During the Mid-Autumn Festival, her figure adorns mooncake boxes, emphasizing her connection to this traditional celebration.

- Evolution of the Chang’e Myth:

Over time, Chang’e’s destiny has garnered more sympathy, with poems expressing both blame for her actions and understanding of her lonely existence on the moon. Today, she is a symbol of beauty and grace, with depictions showcasing her as a goddess embodying these qualities.

- Cultural Significance:

Chang’e’s story is deeply intertwined with the Mid-Autumn Festival. The festival’s origin story often revolves around Chang’e, Yi, and Xiwangmu, providing a reasonable cause for Chang’e’s actions. Families celebrate the festival by offering sacrifices to the moon, symbolizing reunion and harmony. The Chang’e myth continues to be passed down through generations during this festival.

- Character Traits:

Chang’e is described as a kind, smart, and self-sacrificing lady in various versions of her myth. Despite the different motivations attributed to her actions, she remains a central figure in Chinese mythology, embodying both beauty and tragedy.

- Legacy:

Chang’e’s legacy persists in contemporary China, where she is celebrated during the Mid-Autumn Festival. The modern myth combines various fragments, providing a comprehensive and culturally significant narrative that resonates with people of all ages.

Myth and Legend of the Moon Goddess

Legend has it that in ancient times, the sky suddenly bore ten suns, scorching the earth and making life unbearable for the common people. A hero of immense strength, named Hou Yi, resolved to alleviate this suffering. Hou Yi ascended to the summit of Kunlun Mountain, exerted his strength, drew his divine bow to its full capacity, and swiftly shot down nine of the suns. Turning to the last remaining sun, he declared, “From now on, you must rise and set at the designated times, bringing blessings to the people.”

Hou Yi’s heroic act earned him immense respect, and many sought to learn martial arts from him. Among his disciples was a cunning and greedy man named Pang Meng, who joined others in venerating Hou Yi.

Hou Yi’s wife, Chang’e (originally named Heng’e), was a beautiful and kind woman. She often helped the impoverished villagers, earning their affection. One day, the Queen Mother of the West on Kunlun Mountain presented Hou Yi with a pill of immortality. Consuming this pill was believed to grant eternal life and the ability to ascend to the realm of the immortals. However, Hou Yi, unwilling to part with Chang’e, entrusted her to keep the elixir hidden in a treasure box.

Upon ingesting the elixir, Chang’e gracefully ascended into the air. She flew out of the window, over the moonlit countryside, and higher into the azure night sky. The deep blue night sky displayed a bright full moon, and Chang’e continued flying towards it.

When Hou Yi returned home and found his wife Chang’e missing, he anxiously rushed outside. Under the bright moon, with tree shadows swaying gracefully, and a jade rabbit frolicking beneath the trees, he discovered his wife standing next to a cassia tree, gazing affectionately at him. “Chang’e, Chang’e,” Hou Yi called out repeatedly, ignoring all else as he chased after the moon. However, no matter how far he chased, the moon always seemed to move away, and he could never catch up.

The villagers, missing the kind-hearted Chang’e, set out the foods she loved in the courtyard, offering distant blessings. Since then, every fifteenth day of the eighth month became the Mid-Autumn Festival, a time when people eagerly anticipate the joyous reunion of loved ones.

The Mid-Autumn Day and Chang’e

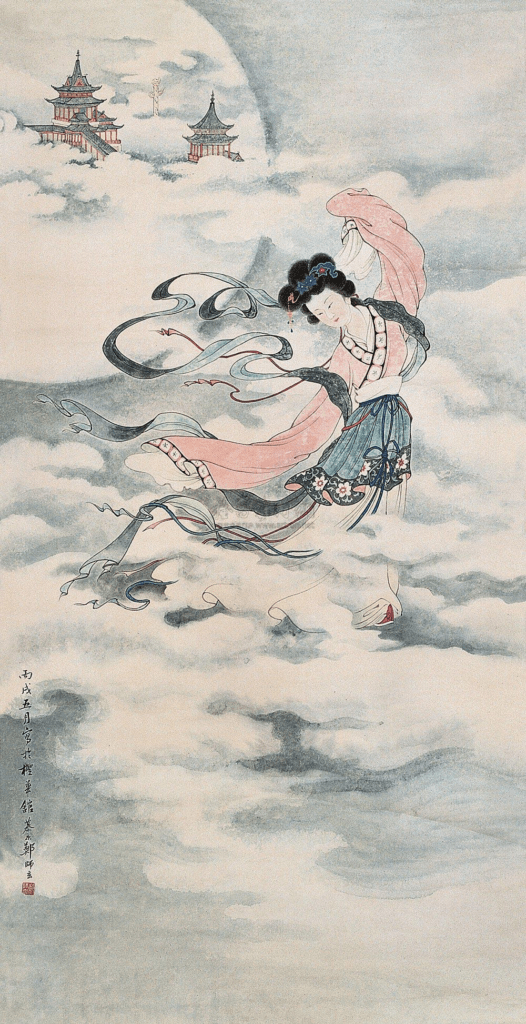

It depicts the twisted branches of a plum tree, the moon goddess Chang’e in wide garments and a long skirt with a fluttering pocket leans against the tree, lost in contemplation.

The Mid-Autumn Festival, also known as “Moon Eve,” “Autumn Festival,” “Mid-Autumn Festival,” “Eighth Month Festival,” “Eighth Month Gathering,” “Chasing the Moon Festival,” “Playing the Moon Festival,” “Worshiping the Moon Festival,” “Daughter’s Festival,” and “Reunion Festival,” is a traditional cultural festival popular among various ethnic groups in the country. It is so named because it falls in the middle of the autumn season.

It is said that on this night, the moon is at its largest, roundest, and brightest. Since ancient times, people have had the custom of feasting and admiring the moon on the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival. Married women who returned to their parents’ homes on this day would always come back to their husbands’ homes, symbolizing completeness and auspiciousness.

The origin of the Mid-Autumn Festival dates back to ancient times, became widespread during the Han Dynasty, took shape in the early years of the Tang Dynasty, flourished after the Song Dynasty, and is now considered one of the four major traditional Chinese festivals alongside the Spring Festival, Qingming Festival, and Dragon Boat Festival.

The Mid-Autumn Festival originated from the worship of celestial phenomena, evolving from the ancient autumn evening moon sacrifices. Since ancient times, the festival has included customs such as moon worship, moon viewing, eating mooncakes, enjoying lanterns, appreciating osmanthus flowers, and drinking osmanthus wine.

According to the “Zhou Li,” during the Zhou Dynasty, there were activities like “welcoming the cold on Mid-Autumn night” and “autumn equinox moon (worshiping the moon).” In the middle of the eighth lunar month, during the harvest of autumn crops, people held a series of ceremonies and celebrations to express gratitude for the protection of deities, known as “autumn reports.”

During the Mid-Autumn season, the temperature is cool but not cold, the sky is clear, and the moon is bright in the middle of the sky, making it the best time to observe the moon. Therefore, the ritual of moon worship gradually gave way to moon viewing, with the sacrificial elements fading, while the festive activities continued and acquired new meanings.

In the Northern Song period, the formal establishment of the fifteenth day of the eighth month as the Mid-Autumn Festival took place. In the Ming and Qing periods, the Mid-Autumn Festival gained equal importance with New Year’s Day, becoming the second-largest traditional festival in China, following closely behind the Spring Festival. Throughout centuries of inheritance and transformation, the festival’s primary cultural significance has evolved into the spirit of “family reunion” that defines the Mid-Autumn Festival today.

Chinese Moon Myth: The Jade Rabbit in the Moon

Beneath a tall wutong tree, two plump white rabbits leisurely frolic in the grass. The rabbits are portrayed realistically, with accurate and vivid forms, each hair delicately depicted to convey a soft texture.

The overall artwork exudes a grand and beautiful atmosphere, influenced by Western painting techniques, showcasing the style of court painting during the Kangxi reign.

Beneath a tall wutong tree, two plump white rabbits leisurely frolic in the grass. The rabbits are portrayed realistically, with accurate and vivid forms, each hair delicately depicted to convey a soft texture.

A long time ago, there were two rabbits who had been cultivating for a thousand years and eventually became immortal. They had four adorable daughters, each born pure and clever.

One day, the Jade Emperor summoned the male rabbit to the Heavenly Palace. As he arrived at the Southern Gate of Heaven, he witnessed Tai Bai Jin Xing, leading celestial soldiers, escorting Chang’e away. Perplexed by the situation, the rabbit asked a nearby heavenly guard about what had happened. Upon hearing Chang’e’s plight, the rabbit felt deep sympathy for her innocent suffering.

The rabbit returned home and shared Chang’e’s story with the female rabbit, expressing a desire to send one of their children to accompany her. The male rabbit earnestly spoke to his family, “If I were lonely and imprisoned, would you be willing to accompany me? Chang’e, for the sake of saving the people, has suffered unfairly. Can we not empathize with her? Children, we must not only think of ourselves!”

Understanding their father’s sentiment, the children expressed their willingness to go. With tears in their eyes, the male and female rabbits smiled, deciding to send their youngest daughter.

The little jade rabbit bid farewell to her parents and sisters, flying to the Moon Palace to accompany Chang’e in her abode.

In the moon, the jade rabbit pounds the elixir of life;

But it was stolen by the goddess Chang’e with one pill.

Since then, the mortal body has transformed into an immortal bone;

Riding the green phoenix, the heavenly wind carries the cassia tree.

月中玉兔捣灵丹,

却被神娥窃一丸。

从此凡胎变仙骨,

天风桂子跨青鸾。

Guanghan Palace

In Chinese mythology, Guanghan Palace(廣寒宮) is a palace located on the moon. It is home to a five-hundred-foot-tall osmanthus tree. The moon gods include Wu Gang(吳剛), Chang’e(嫦娥), and Yutu(玉兔, the rabbit).

The Real Chang’e in Historical Records

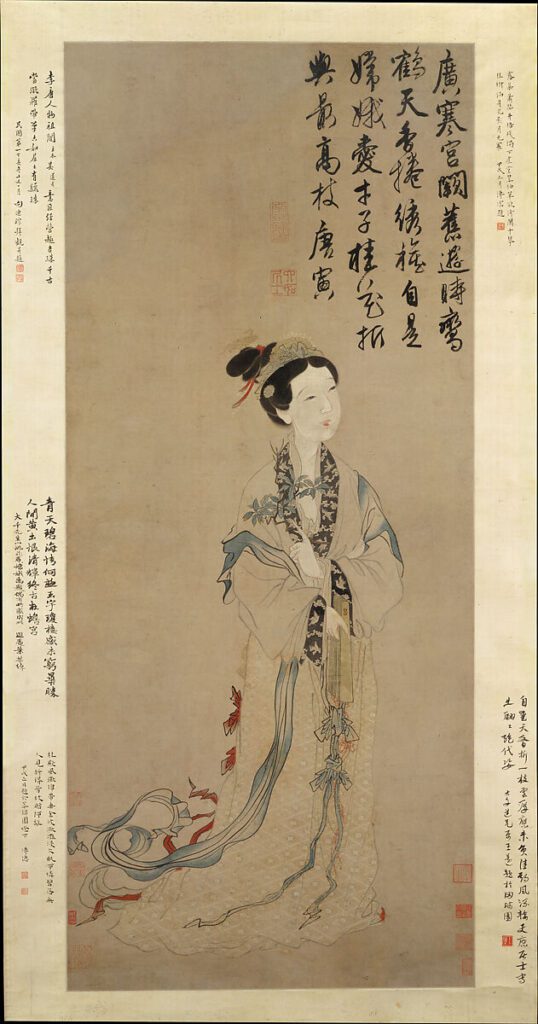

Unidentified artist, in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In Chinese history, there is a prominent figure closely associated with Han Zhu, and she is the well-known Chang’e in Chinese mythology.

Originally named Heng’e, she later adopted the name “Chang’e” to avoid the taboo of Emperor Wen of Han, Liu Heng. The “Book of Poetry” refers to her as “the daughter of Emperor Ku’s subordinate consort.” Historians infer that Heng’e initially married Hou Yi, likely as part of a political alliance between two tribes.

Later, after Han Zhu killed Hou Yi and declared himself king, the tribe to which Heng’e belonged formed an alliance with the Han clan, and she remarried Han Zhu. The sons born to her after this marriage were the “Overlord” Han Jiao and the progenitor of the Ge surname, Han Yi. According to Sun Jingming, a researcher at the Weifang Museum in Shandong, there is a district called Hanting in Weifang City. Over 4,000 years ago, the capital of Han Kingdom, known as “Hanting,” was located here.

The palaces of the Han Kingdom were collectively referred to as the “Han Palace.”

To please Heng’e, Han Zhu built a grander palace for her residence. The term “Guanghan Palace” originated from the vastness (“Guang”) of this palace. The Han clan, also known as the Bomingshi, considered the moon as their totem.

The Chinese myth of “flying to the moon” actually reflects the historical fact of “Han Zhu killing Hou Yi, and Heng’e remarrying Han Zhu.

Chinese Poems about Chang’e

Tang Yin, the artist enamored with beauty, employs delicate and rounded brushstrokes to depict the face, hands, and chest of Chang’e. The clothing, dress, shawl, and waistband are rendered with flowing and folding strokes, a technique that combines angular and rounded elements.

《嫦娥》· 李商隐

云母屏风烛影深,长河渐落晓星沉。

嫦娥应悔偷灵药,碧海青天夜夜心。

“The Moon Goddess” is a poem created by the Tang Dynasty poet Li Shangyin.

The poem laments the lonely scene of Chang’e in the moon as described in the Chinese legend, and expresses the poet’s own feelings of sorrow.

The first two lines describe the indoor and outdoor environments, creating an atmosphere of emptiness and coldness, portraying the protagonist’s contemplative mood.

The last two lines convey the reflections of the protagonist after a night of painful reminiscence, expressing a sense of loneliness. The entire poem carries a melancholic tone, rich in meaning, with imaginative and moving thoughts.

Here is a translation of this poem about Chang’e in English:

The mica screen is stained with a thick layer of candlelight,

The Milky Way gradually slants down and the morning star has sunk.

Chang’e must regret stealing the elixir of life,

Now alone, she is heartbroken every night in the blue sea and sky.

Chang‘e in ‘Journey to the West’

(Japan) preserved in the British Museum. Colour woodblock print. The Chinese woman Chang'e ascending to the moon, where she will become an immortal.](https://weirdtales.me/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/image-685x1024.png)

In Chinese folklore, Chang’e is the celestial goddess within the lunar palace. Among the divine maidens in the Moon Palace, all share the prestigious role of Chang’e.

However, in the original text of “Journey to the West,” only two characters are explicitly named: Su’e Fairy and Ni Chang Fairy.

Su’e Fairy

Su’e, once a celestial maiden in the Moon Palace, gained notoriety for striking the Jade Rabbit. Later, she reincarnated as a princess in the Tianzhu Kingdom, facing unexpected hardships due to the Jade Rabbit’s resentment. Banished to the wilderness by the vengeful rabbit, Su’e sought refuge in a distant temple. To protect herself from the advances of young monks, she endured humiliation, posing as a princess living in squalor.

Ni Chang Fairy

Ni Chang is the one who was teased by Zhu Bajie in “Journey to the West”, and there is no connection between Heng’E (who flying to the moon) and Zhu Bajie.

During the Tang Dynasty, the legend of Ni Chang was intertwined with the moon mythology, featuring the famous “Feathered Robe and Rainbow Skirt Song.” The author of “Journey to the West” likely drew inspiration from this myth, naming a celestial maiden Ni Chang.

FAQs about Chang’e and the Jade Rabbit

1. Who is the Chinese lady in the moon?

The Chinese lady in the moon is Chang’e, a mythical figure in Chinese folklore associated with the Moon Goddess. According to legend, she ascended to the moon after consuming a pill of immortality.

2. Who is the goddess of the moon?

The goddess of the moon in Chinese mythology is Chang’e. She is known for her connection to the Mid-Autumn Festival and her tale of ascending to the moon.

3. Who is the Chinese moon lady myth?

The Chinese moon lady myth revolves around Chang’e, the wife of the hero Hou Yi. The myth explains her journey to the moon after consuming the elixir of immortality.

4. Who is the moon goddess in Chinese folktale?

The moon goddess in Chinese folklore is Chang’e. Her story is intertwined with themes of love, sacrifice, and the origin of the Mid-Autumn Festival.

5. What is the Jade Rabbit?

The Jade Rabbit is a character in Chinese mythology associated with the moon. It is said to pound the elixir of life in the moon and plays a role in the story of Chang’e.

6. Who is Chang’e?

Chang’e is a central figure in Chinese mythology, known as the Moon Goddess. Her story involves her ascent to the moon after consuming the elixir of immortality, symbolizing sacrifice and eternal separation from her husband, Hou Yi.

7. What is the significance of the Mid-Autumn Festival?

The Mid-Autumn Festival, also known as “Moon Eve,” is a traditional Chinese festival celebrating the full moon. It originated from the worship of celestial phenomena and involves customs such as moon worship, moon viewing, eating mooncakes, and family reunions.

8. What is the Jade Rabbit’s role in the moon myth?

The Jade Rabbit in the moon myth is a character that sympathizes with Chang’e’s suffering and sends one of its daughters to accompany her. The Jade Rabbit is known for pounding the elixir of life in the moon.

9. What is Guanghan Palace in Chinese mythology?

Guanghan Palace is a mythical palace located on the moon in Chinese mythology. It is home to various moon gods, including Wu Gang, Chang’e, and the Jade Rabbit.

10. Who was Chang’e in historical records?

In historical records, Chang’e is associated with a prominent figure named Heng’e, who married the hero Hou Yi. After his death, she remarried Han Zhu, and the myth of flying to the moon reflects the historical events of that time.

11. Are there any poems about Chang’e in Chinese literature?

Yes, there are poems about Chang’e in Chinese literature. One notable example is “The Moon Goddess” by Tang Dynasty poet Li Shangyin, expressing sorrow and loneliness associated with Chang’e’s story.

12. How does Chang’e appear in “Journey to the West”?

In “Journey to the West,” Chang’e is portrayed as the celestial goddess within the lunar palace. The celestial maidens in the Moon Palace, including Su’e Fairy and Ni Chang Fairy, share the prestigious role of Chang’e. Su’e Fairy faces hardships due to the Jade Rabbit’s resentment, while Ni Chang Fairy is teased by Zhu Bajie.

13. Is there a connection between Chang’e and Zhu Bajie in “Journey to the West”?

No, there is no direct connection between Chang’e (flying to the moon) and Zhu Bajie in “Journey to the West.” They are separate characters with distinct storylines in Chinese folklore and literature.

Reference

- Birrell, Anne. Chinese Mythology: An Introduction. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993, pp. 144–145.

- Gu, Jiegang. “The Development of Chang’e Story” (in Chinese). Shulin 2 (1979): 33–34.

- Li, Zhonghua. “A Study on the Developing Process of Chang’e Myth” (in Chinese). Sixiang Zhanxian 3 (1997): 19–26.

- Walls, Jan, and Yvonne Walls, eds. and trans. Classical Chinese Myths. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing Co., 1984, pp. 74–76.

- Wen, Yiduo. “An Annotation to the Heaven in Questions of Heaven” (in Chinese). In The Complete Works of Wen Yiduo. Vol. 2. Beijing: Sanlian Shudian, [1948] 1982, pp. 313–338.

- Yuan, Ke. Myths of Ancient China: An Anthology with Annotations (in Chinese). Beijing: Renmin Wenxue Chubanshe, [1979] 1996, pp. 284–286.

- Yuan, Ke. A Survey of Chinese Mythology (in Chinese). Chengdu: Bashu Shushe, 1993, pp. 232–236.