- The Ten Great Tortures – Famous Chinese Torture Methods and Many Others

- Lingchi : The Slow Slicing Execution

- Skinning

- Waist Chop

- Death by Five Horses (Chelie): The Well-known Chinese Torture Methods

- Jufu (All Five Punishments): The Most Influential Chinese Torture Techniques

- Strangulation

- Boiling: Chinese Torture Techniques in Ancient Times

- Palace Punishment

- Amputation

- Needle or Bamboo Stick Insertion

- Live Burial

- Poisoning

- Stick Punishment

- Sawing

- Breaking the Spine

- Lead Pouring

- Combing and Washing

- The Five Punishments – Institutionalized Cruelty in Chinese Torture Techniques

- The End of the Five Chinese Torture Methods and Reforms

- Emperor Wen of Han

- Economic Liberalization and Legal Reforms

- The Abolition of “株连”

- Freedom of Expression and the End of Slanderous Crimes

- Social Transformation of Chinese Torture Methods Triggered by a Daughter’s Courage

- Profound Wisdom in Governing

- Evolution of Chinese Torture Techniques in Later Dynasties

- Qing Dynasty – Fundamental Changes to Corporal Punishment

- Reference

Delving into the annals of ancient Chinese history reveals a grim and unsettling reality – the existence of brutal torture methods that were employed as punishments or tools for extracting confessions.

This historical journey, spanning from the Xia dynasty to the Qing dynasty, unveils a tapestry of disturbing practices, each serving as a testament to the harshness of justice in ancient China.

The Ten Great Tortures – Famous Chinese Torture Methods and Many Others

The Ten Great Tortures were the main expressions of cruel ancient Chinese punishment laws, as well-known Chinese torture techniques. They were the products of an era where legal measures were used as a means of deterrence to uphold the principles of rule. The main contents included skinning, waist chop, death by a thousand cuts, Lingchi (slow slicing), strangulation, boiling, and more. Among them, Lingchi was particularly cruel.

However, with the development of history, these inhumane punishments have become part of the past. Reflecting on the ashes of past dynasties, it raises the question of whether governance should prioritize the severity of punishment or the well-being of the people.

Lingchi : The Slow Slicing Execution

In September 1630, the unfortunate fate of General Yuan Chonghuan unfolded as he faced the merciless lingchi, or “slow slicing,” execution. Accused of collaboration with an invading army, Yuan endured a gruesome spectacle in front of a crowd in Beijing. Ming historian Ji Liuqi documented the horror, describing how Yuan’s body was methodically cut and sliced for hours.

Lingchi was reserved for severe crimes like high treason, leaving a lasting mark on the pages of Chinese history. In Spring and Autumn period, the author of the famous book on the art of war, The Art of War of, Sun Bin, also suffered from Lingchi, the Chinese torture method. His name was changed to Sun “Bian” later on after the punishment. If the kneecap is shaved off, the person loses protection between the thigh and lower leg, making it difficult for them to stand. According to historical anecdotes, after Sun Bin’s amputation, he couldn’t even ride a horse into battle and had to use a carriage (horse-drawn or manually operated).

Skinning

When skinning, a knife is used below the spine to split the back skin into two halves. Slowly, the skin is separated from the muscles, tearing open like a butterfly spreading its wings. The most challenging part is dealing with obese individuals because there is a layer of oil between the skin and muscles that is difficult to separate.

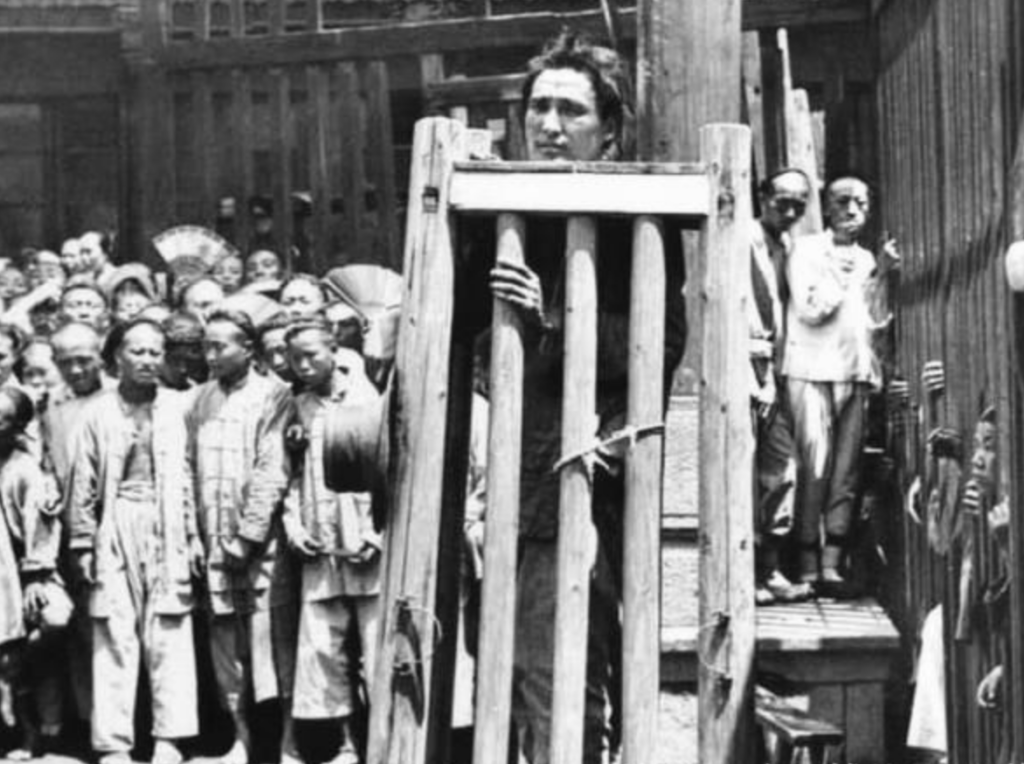

In 1858, an illustration in the French newspaper “Illustration du Monde” depicted the French missionary Maillart being subjected to Lingchi in China. In reality, Maillart died in prison while standing in a cage and was beheaded after death.

Additionally, there is another method of skinning with uncertain credibility among the most cruel Chinese torture methods. The person is buried in the ground, with only the head exposed. A cross is cut on the top of the head, and after pulling apart the scalp, mercury is poured inside. As mercury is heavier than blood, it pulls the muscles and skin apart. The person buried in the ground writhes in pain, unable to escape. Eventually, the body jumps out of the gap, leaving only skin behind in the soil.

Originally, as one of the Chinese torture methods, skinning was done postmortem, but it later evolved into flaying individuals who were still alive.

Waist Chop

Waist chop involves cutting a person in half, and since vital organs are mainly in the upper body, the condemned person doesn’t die immediately. After the chop, they remain conscious, and it takes a considerable amount of time for them to succumb.

Emperor Chengzu of the Ming Dynasty executed Fang Xiaoru using waist chop. Legend has it that after the first cut, Fang Xiaoru crawled with his elbows on the ground, using his bloody hands to write the character “usurp.” It took a total of twenty-four and a half writings before he finally died.

Death by Five Horses (Chelie): The Well-known Chinese Torture Methods

Chelie, as one of the Chinese torture methods, is also known as dismemberment by five horses, it is a simple process where the person is tied by ropes to the head and limbs, and five fast horses pull in different directions, tearing the person into five pieces. It is said that the reformer Shang Yang suffered this punishment.

It takes considerable effort to chop off a person’s head and limbs, let alone using the force of horses. The suffering endured by the condemned is beyond imagination. When the tearing occurs, the person might no longer feel pain. The real agony is during the pulling.

Jufu (All Five Punishments): The Most Influential Chinese Torture Techniques

This Chinese torture technique involves beheading, amputation, hand severing, eye gouging, nose and ear cutting, or “dismemberment into eight pieces.” Usually, after killing the person, their head, limbs, and torso are chopped into three pieces.

After the death of Han Gaozu, Empress Lü ordered the brutal execution of his favorite concubine, Qifu Ren. She had her limbs chopped off, nose, ears, and tongue cut, eyes gouged out, and forced to drink mute-inducing medicine. Ren, unable to speak, was further subjected to smoking her ears to deafness before being thrown into a pigsty, named “human pig.” Later, Empress Lü had her son (Emperor Hui of Han Liu Ying) witness the transformed Qifu Ren. Shocked, Emperor Hui declared it inhumane and was deeply affected, leading to illness and ultimately his death.

Strangulation

In foreign countries, hanging is a commonly used punishment.

In China, hanging is done by strangulation with a bowstring. The bow is placed around the neck of the condemned person, with the bowstring facing forward. The executioner, positioned behind, begins to rotate the bow, tightening it more and more. As the bow tightens, the condemned person’s breath diminishes, and finally, they succumb.

Yue Fei and his son died this way at Fengbo Pavilion (because he was a meritorious official and couldn’t be beheaded, so the body had to be preserved intact). Similarly, the exiled Prince Gui of the Ming Dynasty was strangled by Wu Sangui in the same manner.

Boiling: Chinese Torture Techniques in Ancient Times

Known as “Inviting the Lord into the Cauldron,” this Chinese torture method dates back to the Tang Dynasty when Wu Zetian was the emperor. There was a cruel official named Lai Junchen who advocated harsh punishment and torture for those who refused to confess. The method involved placing a person inside a large cauldron and heating it from below with firewood. As the temperature rose, the suffering of the person inside increased, and if they refused to confess, they would often be burned to death in the cauldron.

Palace Punishment

Palace punishment, also known as castration, was a meticulous process in ancient China. First, a rope was used to tie up the genitals (including the scrotum) to cut off blood circulation, causing natural necrosis. Then, a sharp blade was used to remove the entire genitalia. After the removal, ash was applied to stop bleeding, and a goose feather was inserted into the urethra. After a few days, if urine could be passed, the castration was considered successful. If not, the person was likely to suffer from urinary toxicity and could eventually die. This punishment was often imposed on nobles as an alternative to the death penalty. The female equivalent was seclusion.

Simultaneously, it was through palace punishment that Sima Qian, the historian, wrote the Records of the Grand Historian and expressed phrases like “a person upright serving as a minister in the women’s quarters” in the “Letter to Ren Shaoyou.”

Amputation

Regarding amputation, there are different interpretations. Some say it involves cutting off everything below the knee, while others say it involves shaving the kneecap. The latter is considered more credible. In any case, amputation is a cruel punishment similar to dismemberment.

During the Warring States period, Sun Bin fell victim to a plot by his martial brother and underwent amputation. It is said that his original name was Sun Bin, and it was changed to Sun “Bian” after the punishment. If the kneecap is shaved off, the person loses protection between the thigh and lower leg, making it difficult for them to stand. According to historical anecdotes, after Sun Bin’s amputation, he couldn’t even ride a horse into battle and had to use a carriage (horse-drawn or manually operated).

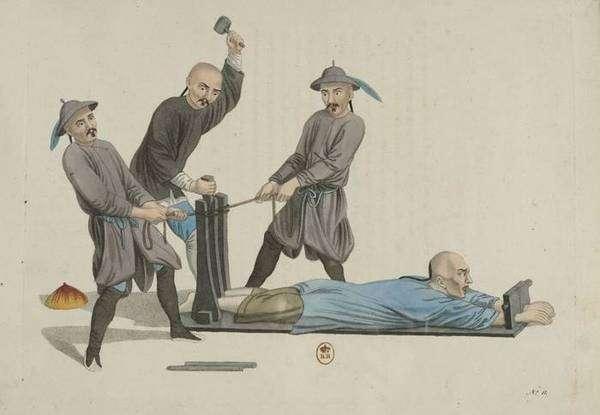

Needle or Bamboo Stick Insertion

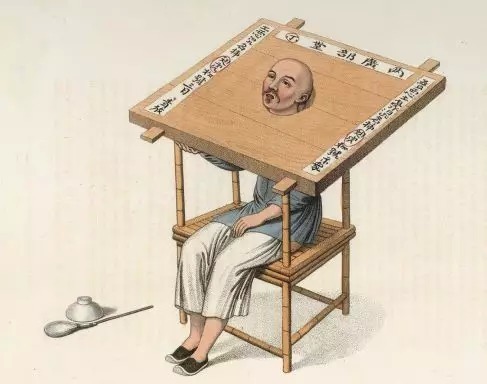

Fixing the prisoner on a torture rack, officials tighten wooden strips around the ankles.

Inserting needles into the gaps between fingernails was a common practice, especially for female prisoners. Bamboo sticks, similar to the toothpicks we often use, were also employed in torture and interrogation. In the Han Dynasty, Xue An, a government official, was ordered to inspect warehouse accounts in Yangzhou. He arrested the warehouse clerk Dai Jiu and forced him to expose the corruption of the county magistrate Cheng Gongfu. They hammered iron needles into Dai Jiu’s fingernails and then forced him to scrape hard soil from the ground. In the early years of the Tang Dynasty, the cruel official Wang Xu often sharpened bamboo sticks and drove them into the fingernails of prisoners, causing excruciating pain.

Live Burial

Live burial is a common method used during war. It is efficient and fast.

In wartime live burials, prisoners of war are often forced to dig their own graves. Sometimes they are killed before being pushed into the pit, but when time is short (or to save bullets), they are pushed in and covered with soil directly. Live burial has a historical presence in Chinese torture methods, though there are no records of notable figures undergoing this punishment. In more severe cases, people are buried straight into the ground with only their heads exposed, and then subjected to torture.

Poisoning

Poisoning is perhaps a comparatively humane method among tortures. …

In ancient China, one of the most famous poisons was ‘鸩’ (zhèn), and the idiom ‘饮鸩止渴’ (drink poison to quench thirst) originates from this. It was commonly used in cases of execution, such as Li Yu and Gao Changgong.

Stick Punishment

Also known as the stake punishment. Here, stick punishment does not involve beating with a stick. Instead, it refers to inserting a stick directly into a person’s mouth or anus, penetrating the stomach and intestines, causing excruciating death.

There are no historical records of this punishment in official history, but it is mentioned in Jin Yong’s novel ‘Xiake Xing’ with the euphemistic name ‘开口笑’ (laughing open). Mo Yan’s ‘Sandalwood Penalty’ also describes this punishment.

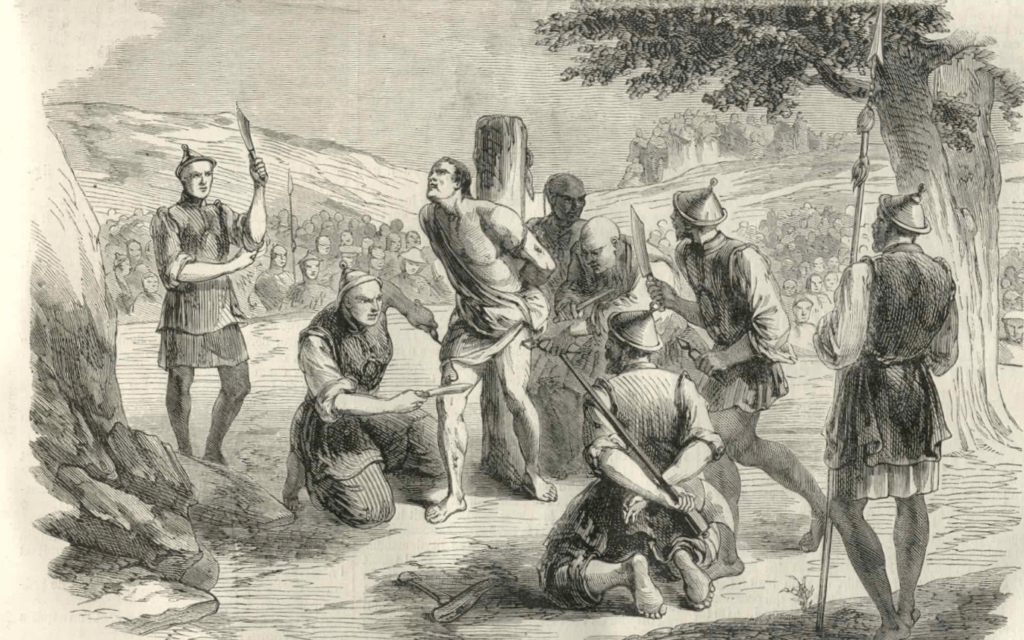

Sawing

Sawing a person to death with an iron saw seems to be on par with Lingchi (slow slicing) and skinning in terms of brutality. It is a torture method specifically depicted in hellish scenarios. However, sawing people alive is not just a legend; it is documented in history.

According to the ‘Records of the Three Kingdoms, Book of Wu, Biography of Sun Hao,’ during the Three Kingdoms period, the beloved concubine of Wu Emperor Sun Hao incited attendants to loot the belongings of the common people. Chen Sheng, in charge of the market trade, caught the robbers and executed them by law. The concubine informed Sun Hao, who, in a fit of rage, falsely accused Chen Sheng of other offenses. Sun Hao ordered the execution of Chen Sheng by sawing off his head with a red-hot saw, and his body was thrown down the market platform.

Breaking the Spine

When one person harbors extreme hatred towards another, they often think of breaking their spine. Breaking the spine was indeed an important torture method in Chinese history. According to the ‘Book of Lord Shang, Section on Rewards and Punishments,’ during the Spring and Autumn period, Ji Zhong’er intended to establish written laws to ensure that everyone in the country abided by them. Together with the ministers, they discussed the case of Minister Dian Ji who arrived late. Some believed Dian Ji was guilty and should be punished. Ji Zhong’er approved, and Dian Ji was executed by breaking the spine.

The aristocrats of the Jin state were terrified, saying, ‘Dian Ji followed Ji Zhong’er in exile for nineteen years, contributing greatly. Now, for a minor offense, he faces such severe punishment. What about us?’ From then on, everyone feared punishment and abided by the law.

Lead Pouring

The man was preparing to get the most severe Chinese torture techniques.

In Buddhist stories about Yama (the lord of the underworld), there is a distinction between the white and black aspects. The white aspect is the ruler of hell, surrounded by beautiful attendants, while the black aspect suffers the torment of lead injection twice a day. Similarly, on Earth, there is the torture of pouring molten tin or lead. Tin has a melting point of 232°C, and lead has a melting point of 327.4°C. Pouring tin or lead can scald a person to death. Furthermore, the melted tin or lead solidifies into hard lumps in the abdomen, and the weight of these heavy metals can also cause death.

During the Han Dynasty, Queen Zhaoxin, the wife of King Liu Qu of Guangchuan, was jealous and cruel. Liu Qu favored another beauty named Rong’ai and often drank with her. Zhaoxin, consumed by jealousy, told Liu Qu, ‘When Rong’ai looks at people, her expression seems abnormal. She probably has an affair with someone.’ Believing it to be true, Liu Qu, in a fit of anger, took the clothes Rong’ai was embroidering for him, threw them into the fire, and burned them. Terrified, Rong’ai sought death by jumping into a well, but Liu Qu ordered her rescue.

Unfortunately, she did not die. Liu Qu punished Rong’ai by whipping her, forcing her to confess to the alleged affair. Unable to withstand the torture, Rong’ai randomly mentioned having an affair with a physician. Liu Qu became more enraged, tied Rong’ai to a pillar, used a red-hot knife to gouge out her eyes, cut the flesh from her thighs, and finally poured melted lead into her mouth, tormenting Rong’ai until her death.

Combing and Washing

The term ‘combing and washing’ here does not refer to the grooming of women but to an extremely cruel form of punishment. It involves using an iron brush to scrape away a person’s flesh, one layer at a time, until the bones are exposed, ultimately causing death.

The true inventor of this torture was Zhu Yuanzhang. According to Shen Wen’s ‘Record of the Early Governance of the Sage King,’ when implementing the punishment of combing and washing, the executioner would strip the prisoner naked, place them on an iron bed, pour boiling water over them several times, and then use an iron brush to scrape away the flesh from their body, similar to scalding a pig with boiling water before removing its hair.

This process continues until the flesh is completely scraped away, revealing the white bones. However, the victim usually dies long before reaching that point. The punishment of combing and washing is similar in its gruesome nature to Lingchi.

The Five Punishments – Institutionalized Cruelty in Chinese Torture Techniques

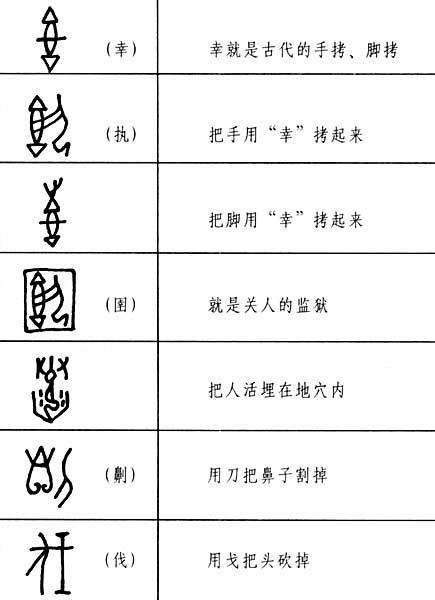

During the Xia Dynasty, practices such as “Mo” (tattooing on the face), “Yi” (cutting off the nose), “Fei” (later changed to “Yue,” “Yue,” and “Bing,” involving amputation of the legs during the Zhou Dynasty), “Gong,” and “Da Bi” (capital punishment) formed the so-called “Five Punishments” system, which was later inherited by future generations.

As early as the Xia dynasty, physical punishment played a crucial role in maintaining political order, as main Chinese torture techniques. The Book of Han highlighted the “five punishments,” including face tattooing, nose cutting, foot amputation, removal of reproductive organs, and death. Crimes varied from disobedience to theft, each associated with a specific punishment. The cruelty reached its peak during the Qin dynasty where Qin Shihuang ruled, with colorful execution methods such as boiling alive, public beheading, and chariot dragging.

The End of the Five Chinese Torture Methods and Reforms

Emperor Wen of the Han dynasty initiated reforms to the punitive system, influenced by the courageous appeal of Chunyu Tiying. Her plea led to the abolition of the five punishments, replaced by flogging, penal servitude, and hair-cutting as alternative forms of retribution.

Emperor Wen of Han

In the annals of Chinese history, Emperor Wen of Han, Liu Heng, stands out as a visionary ruler who ushered in a transformative era marked by benevolent governance and groundbreaking legal reforms. Among his notable achievements was the abolition of cruel corporal punishment, a move that significantly shaped the civilization of penal systems in ancient China.

Economic Liberalization and Legal Reforms

Emperor Wen of Han, known for his “kuanren” or benevolence, extended his compassionate approach not only to the economic well-being of his subjects but also to the legal realm. Rejecting the Legalist doctrine of “heavy penalties for minor offenses,” he embarked on a groundbreaking legal reform, becoming the sole emperor in feudal China to abolish the brutal practice of corporal punishment.

Embracing the teachings of Huang-Lao, Emperor Wen advocated for a “righteous ruler” and a “righteous law.” Under his guidance, a series of legal reforms unfolded, starting with the abolition of the “guilt by association” system, colloquially known as “株连” or “zhu lian.” This ancient Chinese practice involved punishing not only the perpetrator of a crime but also their family members and even a broader circle of relatives.

The Abolition of “株连”

In a decisive decree issued in December of 179 B.C., Emperor Wen challenged the prevailing views of his advisors and ministers, expressing his concerns about the unjust implications of the “guilt by association” system. Despite initial resistance, he stood firm, leading to the immediate dismantling of this controversial practice.

Freedom of Expression and the End of Slanderous Crimes

Emperor Wen of Han’s commitment to enlightened governance extended beyond legal reforms. He sought to create a society where freedom of expression flourished, even to the extent of allowing criticisms and insults against the emperor without consequence. This progressive stance was a departure from the ancient crime of “大不敬” or lese-majeste, which restricted discussions about the emperor and was exploited as a tool for suppressing dissent.

In a bold move in 178 B.C., Emperor Wen issued a decree abolishing crimes related to rumors and slander. He acknowledged the importance of open discourse in governance, recognizing that restricting opinions would hinder the identification of flaws and the attraction of talented advisors. This act paved the way for a more open political atmosphere and the selection of competent individuals into government service.

Social Transformation of Chinese Torture Methods Triggered by a Daughter’s Courage

The shift away from primitive and brutal “肉刑” or corporeal punishment was underscored by a poignant event known as the “缇萦上书” or “Ti Ying Petition.” In 167 B.C., Chunyu Ti Ying, a courageous young girl, challenged the prevailing notion of corporeal punishment when her father, Chunyu Yi, faced unjust accusations. Ti Ying’s heartfelt petition moved Emperor Wen, leading to the abolition of corporeal punishment and the implementation of benevolent governance.

Profound Wisdom in Governing

Emperor Wen’s decision to abolish corporeal punishment wasn’t arbitrary; it was rooted in a deep understanding of the social background. The Qin Dynasty’s harsh penal system, inherited by the Han Dynasty, had created an environment of brutality. The abolition of corporeal punishment, with its exaggerated descriptions of cruelty, became a necessity for social progress and governance.

Despite these changes, the Sui and Tang dynasties introduced a new set of five penalties, emphasizing beating, penal servitude, exile, and death.

Evolution of Chinese Torture Techniques in Later Dynasties

From 1644 to 1911, the judicial system of the Qing Dynasty advanced rapidly towards modernization. Signs of reducing extreme corporal punishments had begun to emerge.

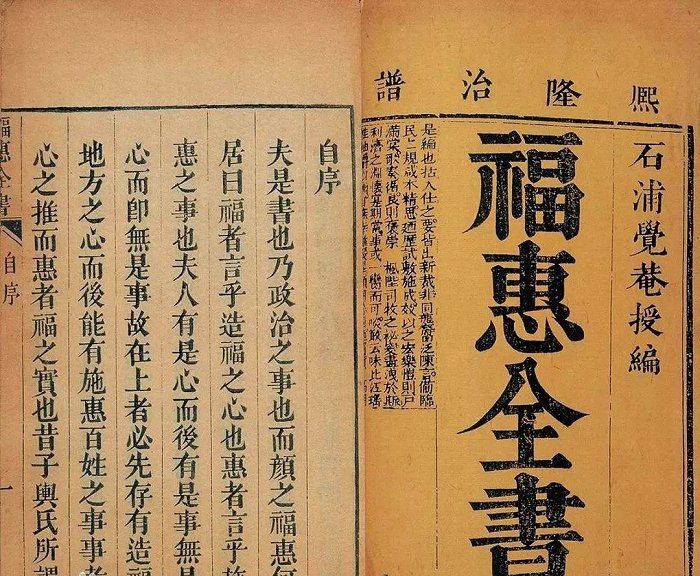

During this period, the “Fuhui Quanshu,” first published in 1699, became a guide for local administrative officials in convicting and sentencing. Huang Liuhong, one of the hundred local administrative officials in 17th-century China and the author, pointed out, “The instruments of punishment used today are lighter than those of the past… for disciplinary purposes, bamboo should be used.”

Though the most vicious corporal punishments diminished, torture techniques persisted. The Ming dynasty’s secret police, known as the “Embroidered Uniform Guard,” utilized cruel devices like the ankle crusher and finger squeezer to extract confessions. Iron shoes, heated until red-hot and forced onto suspects’ feet, added a creative yet agonizing dimension to the torture repertoire.

Qing Dynasty – Fundamental Changes to Corporal Punishment

The Qing dynasty witnessed significant changes in corporal punishment, with the abolition of the five penalties from the Sui and Tang dynasties. By the mid-1600s, only flogging remained as an official physical punishment, alongside the death penalty for serious offenses. Emperor Guangxu’s 1904 decree marked the final blow to flogging, officially ending the era of slow slicing in 1905, a staggering 275 years after Yuan Chonghuan’s tragic fate.

Reference

- Extraordinary Legal History: Legal Anecdotes Throughout History, Author: Liu Dian.《非常法史:历史上的法律趣事》 作者:刘典